In an article that appeared in NPR, of all places, below the headline, “Why some doctors have started asking patients about their spiritual lives.”

Timothy Moss was forced to retire from his teaching gig at age 59 after suffering from a raft of sudden and unexpected “health complications” (heart and kidney problems, neuropathy, and vision issues). After that, his brother died. Ahem. (💉 alert.)

Without a job, Mr. Moss —who is apparently single and childless— found himself utterly alone. His work had been his whole life. He had nothing left. “I loved my job. That was my hobby. It was all my friendships,” he told NPR.

Up to this point, it was the classic tragedy of liberalism. Absent a career, Moss had no purpose. His career was (probably) deleted by his trust in government and the experimental injections he believed were good for him. He faced nothing but misery from his health problems, loneliness, and despair.

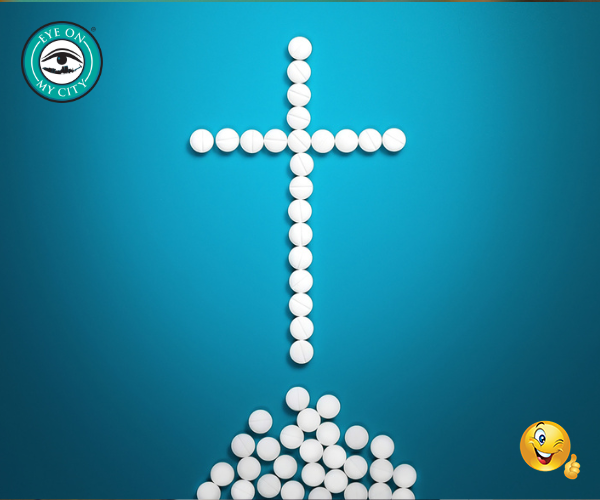

There’s no drug for that.

But there was something for Moss’s condition. Under a unique Indiana University Health system program called the Congregational Care Network, hospital employees connected Mr. Moss with a faith-based group.

🔥 IU Health’s program starts with a doctor asking patients a series of “spiritual assessment” questions aimed to identify if they need something beyond their immediate physical care.

“All human beings have a need for meaning and purpose,” Jay Foster, the Vice President of Spiritual Care at IU Health, said. “When someone has an illness, that sense of meaning and purpose is impinged upon, and having a thoughtful conversation partner can help people cope with that illness.”

Foster pointed to a recent report from the McKinsey Health Institute which found that “spiritual meaning in one’s life” was associated with strong mental, physical, and social health. Who knew.

So far, the IU program remains a sample of one, but there are signs of an increasing recognition of spiritual needs in health care. At the most recent annual meeting of the American Medical Association, for instance, delegates passed a resolution promoting medical education on spiritual health and supporting patient access to spiritual care services.

None of this surprises Christian believers.

Secular readers may struggle to understand, but a rich spiritual life delivers meaning in a way that nothing else in the world can. For believers, you can strip away everything material —job, friends, family— and meaning persists.

According to Christian understanding, while imperfect, the church writ large is God’s gift to believers, for mutual support, encouragement, service, social fulfillment, and mutual growth in faith, love, and good deeds. It’s a place not only to receive support in times of need, but also to give support to other needful believers.

You can easily imagine the afterlife conversation between God and somebody like Mr. Moss. “But I had nothing,” the ghostly human complains, adding “nobody liked me. Even my cat ran away.” God rolls his eyes in frustration and says, “For Heaven’s sake, I gave you a free social club with a billion people in it; it had no dues and they were required to accept everyapplicant. It was literally right down the street. All you had to do was walk in the door. Seriously, must I do everything around here?”

Our collective pandemic experience continues changing us in ways nobody could predict. Doctors themselves are not immune to the empty, failed promises of their profession. Like the rest of us, they used to blindly trust the big institutions that seemed to offer everyone meaning, but which the pandemic exposed to be just as flawed and untrustworthy as any other human institution.

Now doctors are asking the big questions: is this all there is? If the IU program can be seen as a sign, some medical professionals are starting to realize that truth cannot come from a pill bottle, ‘consensus,’ or a professional organization. This story sits at the intersection of lost institutional trust, religious revival, our fundamental understanding of health care and what it means to be human, and a very positive sign of grasping for a way out of our cultural dead end.

Even five years ago, doctors were happy to ask patients about their sex lives and illegal drug use, but about religion? Too icky.

Maybe it’s nothing. Or maybe this is a fascinating and encouraging development.