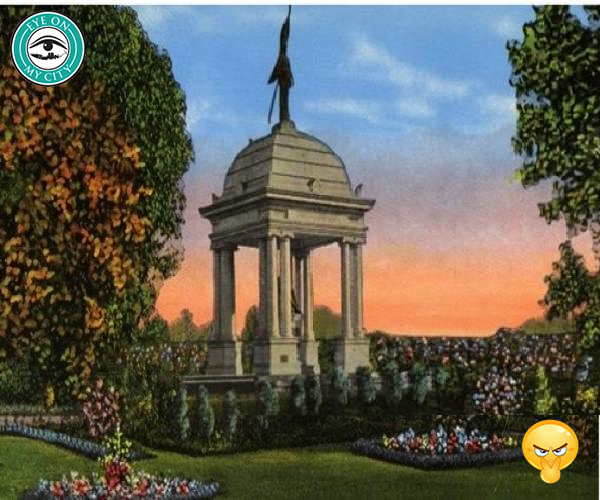

One victim of the cancel culture is the bronze statue of a Confederate soldier that stood in what is now, after a vote by the City Council, James Weldon Johnson Park.

The figure was spirited away to a secret location in the dead of night by politicians seeking to appease the Angry Left, probably in the hope of avoiding riots, looting and burning in Jacksonville.

Mayor Lenny Curry said the following day, “If our history prevents us from reaching the full potential of our future, then we need to take action. Last night, I ordered the confederate statue in Hemming Park to be taken down as the start of a commitment to everyone in our city that we will find a way to respect each other and thrive.”

There are some who doubt that the figure even represents a Confederate soldier. What irony that would be, if true.

One person told Eye that he has inspected the statue and the uniform does not seem to match the Confederate uniform.

This is contrary to the History of Jacksonville by T. Frederick Davis, which says, “The figure in bronze standing guard on top of the monument in Hemming Park, represents a soldier in the uniform of the Southern Confederacy. He wears no insignia or device that can be detected from the sidewalk; but there is one, on his cap above the visor, the letters “J. L. I.”

J.L.I. stands for Jacksonville Light Infantry, a local military outfit that fought in three wars.

The city did not play much part in what has been called the Civil War, War Between the States and, in jest, the War of Northern Aggression.

Jacksonville surrendered to the Union Army March 12, 1862, when the sheriff turned it over to a Union commander in the hope of sparing it from destruction.

Jacksonville was occupied by Federal troops four times, the third time March 10, 1863, this time by negro troops commanded by white officers. No major battles were fought but there were occasional skirmishes and casualties.

In the early days of Jacksonville, storms backed water into the stores on Bay Street. One of the city’s founders, I. D. Hart, attempted to correct this (and at the same time increase the value of a larger section of his property) in his survey of the city by moving the business center of the town from Bay Street to a black-jack ridge, where he provided a public square. The executors of Hart’s estate donated this square to the city in 1866.

In 1887, $700 was set aside for the park. Walks were laid and a well dug in the center for a flowing fountain. The fountain was moved in 1898 to make way for the Confederate monument.

At first the two-acre site was called simply City Park; then St. James Park after the St. James Building was erected on its north side. As a memorial to Charles C. Hemming, a former soldier in the J.L.I. who gave the Confederate monument, the name was officially changed to Hemming Park on Oct. 26, 1899.

The Confederate monument was unveiled June 16, 1898, by Miss Sarah Elizabeth Call, accompanied by a salute of thirteen guns. Taking part in the ceremonies were regiments of both Southern and Northern veterans. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee was in the reviewing stand, while a grandson of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant stood on the piazza of the Windsor Hotel west of the park.

“Thus both the North and the South were represented in the unveiling of this monument to the valor of the Confederate soldiers of Florida,” Davis said.

Three years after being erected, the statue survived the Great Fire of 1901, which destroyed most of downtown.

“The monument in Hemming Park, although centered in the hottest part of the fire, went through it all unscathed. About its base had been placed pile upon pile of household goods, and when these burned, fury and heat were added to that of the surrounding burning blocks; but only the cement at the base of the monument showed a reddened glow.

“The bronze soldier at the top stood firm amidst the withering torrent of fire about him.” Davis wrote.

But a figure meant as a memorial to war dead became swept up in politics and the “cancel culture” that is seeking to revise and rewrite U.S. history demanded, and got, its removal and the park’s name change.

Johnson is the Jacksonville resident who was a lawyer, author, editorial writer and head of the NAACP. He wrote the lyrics to “Lift Ev’ry Heart and Sing.”

Along with this change comes demands to change school names, other park names and perhaps even the city’s name. No one knows where, or when, it will end.

“History is always written by the winners. When two cultures clash, the loser is obliterated, and the winner writes the history books – books which glorify their own cause and disparage the conquered foe. As Napoleon once said, ‘What is history, but a fable agreed upon?’ ” ― Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code